10 Interpolation Revisited - Splines

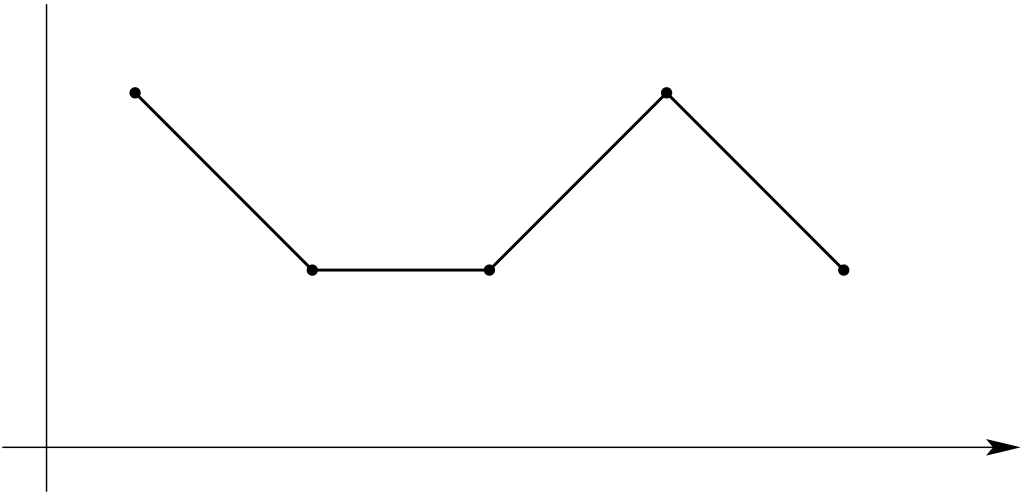

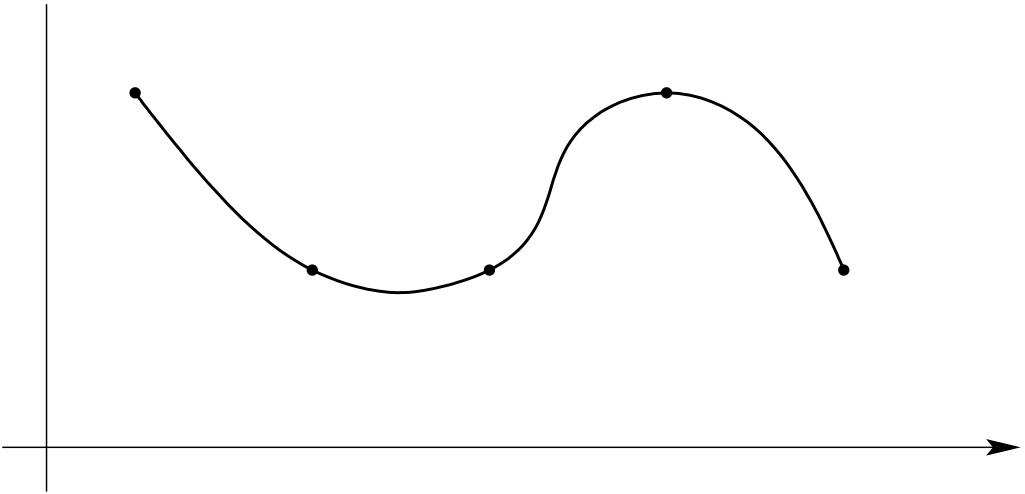

In this chapter, we will discuss the so-called spline interpolation. In order to avoid the overshooting/undershooting related to higher order polynomial approximation, we will replace the global interpolation polynomial on \([a,b]\) with interpolation polynomials of lower order on sub-intervals of \([a,b].\) At the interfaces between the sub-intervals, we have to ensure the continuity of our interpolant and of its derivatives. For examples, see Figure 10.1.

Of particular interest will be the cubic spline interpolation. For cubic splines, we will build our interpolant using piecewise cubic polynomials. At the sub-interval interfaces, we will require continuity of the interpolant and its derivative up to the second order. In this way, we can combine our goal of reducing over-/under-shooting with a smooth-looking interpolant.

10.1 Piecewise Linear Interpolation

We start by recalling the ideas for piecewise linear interpolation from Chapter 6. In Section 6.7, we have used linear functions on the sub-intervals of \([x_i,x_{i+1}]\subseteq [a,b],\) leading to the space of continuous and piecewise linear functions on \([a,b]\) \[U_n \;=\; S_n \;=\; \left\{v \;|\; v \in C([a,b]), \; v|_{[x_{k-1},x_k]} \in P_1, \, k = 1,\ldots, n\right\}\, .\]

The interpolation problem \[u_n \in S_n:\;u_n(x_k)\;=\;f(x_k),\qquad k=0,\ldots, n\] has solution \[\begin{aligned} u_n \;&=\; \sum_{k=0}^n f(x_k) \varphi_k\\ \text{with } \varphi_k\in S_n \text{ fulfilling } \varphi_k (x_l) \;&=\; \delta_{kl}\, , \end{aligned}\] the so-called nodal basis.

We would like to investigate this construction in more detail

on each sub-interval \([x_{k-1},x_k]\) we took polynomials of first order for building the interpolant. In principle, with \(2\) degrees of freedom per sub-interval, we would have in total \(2n\) degrees of freedom.

the polynomials on the sub-intervals were “glued” together by the condition \(v \in C([a,b]),\) i.e. by requiring global continuity. This condition removes one degree of freedom at each interface, leading to \(2n-(n-1)=n+1\) remaining degrees of freedom.

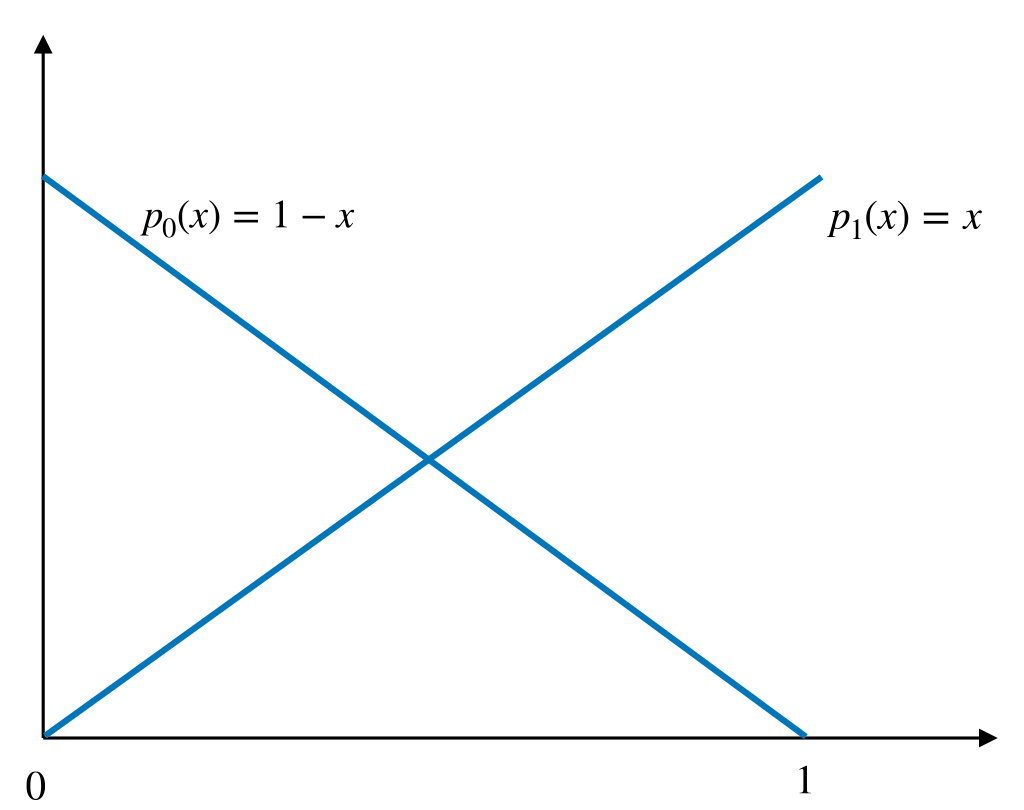

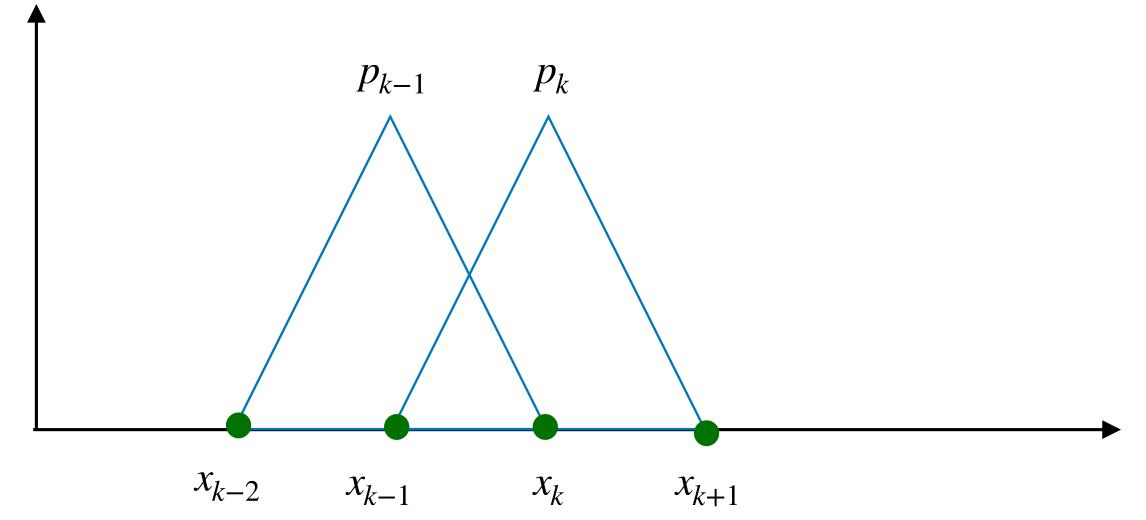

Our interpolant was eventually expressed as a linear combination of the nodal basis functions (hat functions). The hat function at point \(x_k\) can be constructed as the sum of two Lagrangian basis functions of \(P_1([x_{k-1},x_k])\) and \(P_1([x_{k},x_k+1]),\) respectively.

Figure 10.2 illustrates this connection process: two Lagrangian basis functions (left picture) get connected, such that the resulting (hat) function (right picture) is continuous. We call the hat functions also nodal basis functions.

10.2 Cubic Spline Interpolation

The motivation to define the cubic spline interpolation is the increase of the global smoothness of the interpolating function. In this context, the “smoothness” of the interpolant \(\phi\) can be interpreted as cumulative curvature.

Let \(\Delta=\{ a=x_0<x_1<\cdots<x_n=b\}\) be a set of nodes. We set \(I_k=[x_{k},x_{k+1}]\) and \(h_k=x_{k+1}-x_{k},\) \(k=0, \ldots, n-1.\) We now incorporate the smooth transition at the borders between the sub-intervals into our problem formulation.

We will denote by \(C^{m}([a,b])\) the space of all functions with \(m\) continuous derivatives on the interval \([a,b].\)

The spline functions of order \(m\) for the mesh \(\Delta\) are defined by \[S_{\Delta}^m \;=\; \left\{ v \in C^{m-1}([a,b]),\; v|_{I_k} = S_k \in P^m\right\}.\] The case \(m=3\) is called cubic splines.

We now consider the interpolation problem \[\tag{10.1} s\in S_{\Delta}^m:\;s(x_k) \;=\; f(x_k)\qquad \forall k=0,\ldots, n.\]

Each \(v\in S_{\Delta}^m\) is determined by \(n\) polynomials \(S_k,\) \(k=0,\ldots, n-1\) of order \(m,\) leading to a total of \(n \cdot (m+1)\) coefficients. The requirement \(v\in C^{m-1}\) gives rise to \(m \cdot (n-1)\) interface conditions: \[S_k^{(j)}(x_{k+1}) \;=\; S_{k+1}^{(j)}(x_{k+1}),\qquad j=0, \ldots, m-1,\;k = 0, \ldots, n-2\]

The resulting equations for the coefficients of the local polynomials \(S_k,\) \(k=0, \ldots, n-1\) can be shown to be linearly independent which here, however, we do not show. Thus, we get \[\dim S_{\Delta}^m \;=\; n(m+1)-(n-1)m \;=\; n+m\] We have \(n+1\) interpolation conditions from (10.1). Since we have \[\dim S_{\Delta}^m-(n+1) \;=\; m-1,\] we have to prescribe additional \(m-1\) conditions.

For the case \(m=1\) we have \(m-1=0,\) so no additional conditions have to be imposed. However, for the case \(m=3\) (cubic splines) we need \(m-1=2\) additional conditions. This is normally done via boundary conditions at \(a\) and \(b.\) The most commonly used ones are

natural boundary conditions: \(s^{\prime\prime}(a) = s^{\prime\prime}(b) = 0.\)

prescribed boundary derivatives: \(s^\prime(a) = f_0^\prime\) and \(s^\prime(b) = f_n^\prime,\) where \(f_0^\prime\) and \(f_n^\prime\) are prescribed values of either the function’s actual derivative or an approximation thereof.

periodic boundary conditions: \(s(a) = s(b)\) and \(s^\prime(a) = s^\prime(b).\)

10.3 A Mechanical Motivation

The content of this subsection is for motivational purposes and can be ignored on first reading. The following arguments explain why the name “spline” has been chosen.

Consider a spline \[\psi \in C_{\Delta}^2([a,b]) \;=\; \left\{ v \in C^2([a,b]),\; v(x_k) = f(x_k), k = 0,\ldots, n \right\}\] described by the nodes \((x_k, f(x_k))\) with prescribed boundary derivatives. The mean curvature of \(\psi\) is defined by \[{\mathcal K}(x) \;=\; \frac{\psi^{\prime\prime}(x)}{(1+\psi^\prime(x)^2)^{3/2}}\]

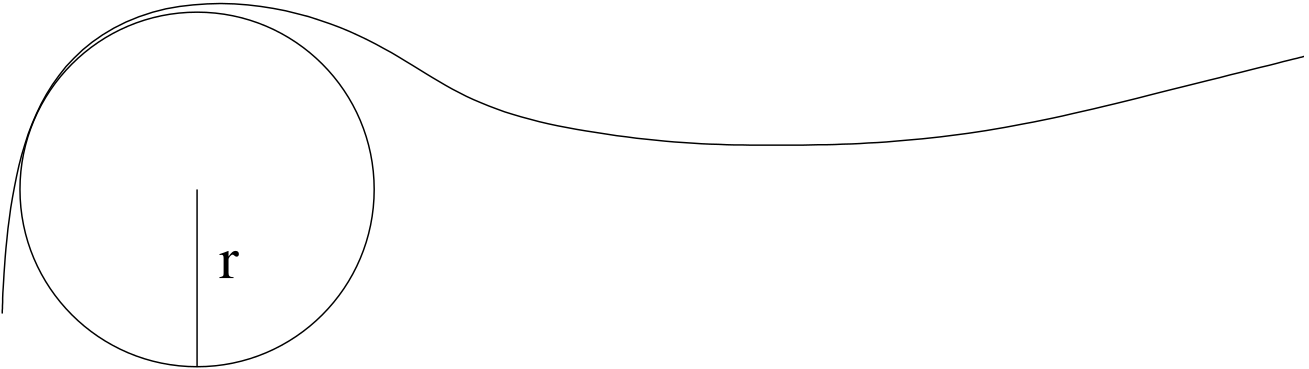

Curvature can also be interpreted as the radius \(r\) of an osculating circle, cf. Figure 10.3 by the relation \(|{\mathcal K}(x)| = \frac{1}{r}.\)

For small displacements, we have \({\mathcal K}(x) \approx \psi^{\prime\prime}(x)\) and we can measure the elastic energy or bending energy of the spline by means of \[E(\psi) \;=\; \int_a^b \, (\psi^{\prime\prime})^2 \, \approx \int_a^b \, ({\mathcal K}(x))^2 \, dx.\] The elastic energy \(E\) should be minimal on the set of all possible configurations of the spline, which fulfill the natural boundary conditions. Technically, this means that we are looking for a function \(\psi\) in the set \[H \;=\; \left\{ v \in C_{\Delta}^2([a,b]),\; v^{\prime}(a) = f^{\prime}(a),\; v^{\prime}(b) = f^{\prime}(b)\right\}\,\] which has minimal elastic energy \(E(\psi).\) Setting \(\|v\|_{L^2}^2 := \int_a^b \, v^2 \, dx,\) we thus get the minimization problem \[\text{Find } \psi \in H: \; \left\|\psi^{\prime\prime}\right\|_{L^2} \;\leq\; \left\|v^{\prime\prime}\right\|_{L^2} \qquad \forall v \in H.\]

Let \(s \in S_{\Delta}^3\) be the solution of the interpolation problem (10.1) and let \(v \in C_{\Delta}^2([a,b]).\) Then, if \[\tag{10.2} s^{\prime\prime}(x) \left.\left(v^{\prime}(x)-s^{\prime}(x)\right) \right\rvert_a^b \;=\; 0\] we get the estimate \[\tag{10.3} \left\|s^{\prime\prime}\right\|_{L^2} \;\leq\; \left\|v^{\prime\prime}\right\|_{L^2}\]

The above theorem states nothing less than that the spline interpolation is the function with the smallest second derivative that fulfills the interpolation conditions. Thus, it avoids over- and under-shooting.

10.4 Computing a cubic spline

Up to now, we have just looked at splines from a purely theoretical point of view. We have stated neither a precise expression for one nor a way to compute its coefficients. The spline \(s\in S_\Delta^n\) is actually made up of \(n\) separate parts \(S_i,\) \(0\leq i\leq n-1,\) which are defined on \([x_i,x_{i+1}].\) These are cubic polynomials.

First, let us assume we have a set of nodes \(x_0 < x_1 < \ldots < x_n\) with \(x_i\in[a,b],\) \(x_0=a\) and \(x_n=b.\) We define their differences \(h_i\) by \(h_i = x_{i+1} - x_i.\) We can now write the \(S_i\) as follows: \[\begin{aligned} S_i(x) \;=\quad a_i + b_i(x-x_i)+\frac{c_i}{2}(x-x_i)^2+\frac{d_i}{6}(x-x_i)^3 \end{aligned}\] We now need to take care of the transition condition between the sub-intervals. This is a good exercise in bookkeeping.

10.4.0.0.1 Continuity and Interpolation Conditions

We get \(2n\) conditions, since for \(i=0,\ldots,n-1\) it holds \[\begin{aligned} S_i(x_i)=y_i \end{aligned}\] Leading to \[\tag{10.4} \begin{aligned} S_i(x_i) &= y_i = a_i \qquad\text{left end-point}\\ S_i(x_{i+1}) &= y_{i+1} = a_i+b_i h_i +\frac{c_i}{2} h_i^2 +\frac{d_i}{6}h_i^3 \qquad\text{right end-point} \end{aligned}\]

10.4.0.0.2 Continuity of the First Derivative

We get \(n-1\) conditions, since for \(i=0,\ldots,n-2\) it holds at the inner points \[\tag{10.5} \begin{aligned} S_i'(x_{i+1}) &= S_{i+1}'(x_{i+1}) = b_i + c_i h_i +\frac{d_i}{2} h_i^2 = b _{i+1} \end{aligned}\]

10.4.0.0.3 Continuity of the Second Derivative

We get \(n-1\) conditions, since for \(i=0,\ldots,n-2\) it holds at the inner points \[\tag{10.6} \begin{aligned} S_i''(x_{i+1}) &= S_{i+1}''(x_{i+1}) = c_i + d_i h_i = c_{i+1} \end{aligned}\]

10.4.0.0.4 Boundary Conditions

We get \(2\) conditions, at the boundary points from the boundary conditions. Here, we took natural boundary conditions. \[\begin{aligned} S_0''(x_0) &= 0 = c_0\\ S_{n-1}''(x_n) &= 0 = c_{n-1}+d_{n-1}h_{n-1} \end{aligned}\] We then use (10.6) and (10.4) to define \(d_i\) and \(b_i\) respectively and substitute them into (10.5). This leads to the following equation for \(i=0,\ldots,n-2\) \[\tag{10.7} h_ic_i+2(h_{i+1}+h_i)c_{i+1} + h_{i+1}c_{i+2} = 6\left(\frac{y_{i+2}-y_{i+1}}{h_{i+1}} - \frac{y_{i+1}-y_{i}}{h_{i}} \right)\, .\] For the ease of notation, we have set \(c_n=0.\)

For equidistant nodes with \(h_i=h\) we get \[hc_i+4hc_{i+1}+hc_{i+2} = \frac{6}{h}(y_{i+2}-2y_{i+1}+y_i)\] which we can write with \(k=i+1\) for easier indexing as \[hc_{k-1}+4hc_{k}+hc_{k+1} = \frac{6}{h}(y_{k+1}-2y_{k}+y_{k-1})\, .\] The resulting linear system then is tri-diagonal and can be solved with, e.g. Gaussian elimination, for the coefficients \(c_i.\) The remaining coefficients \(a_i,d_i,b_i\) can then be computed for \(i=0,\ldots,n-1\) with the elementary formulas \[\begin{aligned} a_i&=y_i\\ d_i &= \frac{c_{i+1}-c_i}{h_i}\\ b_i&= \frac{y_{i+1}-y_i}{h_i} - \frac{1}{2}c_ih_i-\frac{1}{6}d_ih_i^2 \end{aligned}\] For example, for an equidistant mesh, we would get for the coefficient matrix \(H\) from (10.7) \[H \;=\; \begin{pmatrix} 4h & h \\ h & 4h & & h && 0 \\ 0 & h & & 4h && h && 0 \\ & & \ddots & & \ddots & & \ddots \\ & 0 && h && 4h && h \\ & && & & h && 4h \end{pmatrix}\]