Optimization and machine learning are distinct topics, and one could easily dedicate entire separate courses to each of them. There is however a strong connection between the two: the learning step of most machine learning algorithms involves solving an optimization problem. Optimization problems also arise in science, engineering, economics, applied mathematics, etc.

Optimization

The problem \[\text{``What is the maximal value of }\:f(x)=x^{2}-x^{4}\text{?''}\tag{1.1}\] is a basic example of an optimization problem. This very simple problem can be solved by hand, or “visually” using the following graph.

A more complicated type of problem which we will study is the optimization of functions of several variables, which are subject to constraints. We will also consider large scale optimization problems over say millions of variables of the type \[\text{``What is the maximal value of }f(x_{1},\ldots,x_{10^{6}})\text{?''}\] Unless \(f\) has some special structure that can be exploited, such a problem can not be solved by hand. We will study numerical optimization algorithms for such such problems.

Machine learning

Machine learning is about algorithms that can be taught to carry out tasks, instead of being explicitly programmed with the exact detailed steps needed to carry out each possible variation of the task, as in traditional programming. Many such tasks can be formulated in terms of producing a desired output when presented with an input, to be learned from a dataset of input-output pairs created by humans. A very simple machine learning algorithm for this type of task is linear regression. For instance, if one has a dataset of floor area of apartments (input) together with their rent (output) for a certain neighborhood, one can find the linear function that best fits the data, and use it to predict the rent of future apartments in the neighborhood. See Figure Figure 1.2.

Despite its simplicity linear regression is indeed a machine learning algorithm. It can also be considered a statistical tool - indeed machine learning and statistics have a lot in common.

Finding the best fitting line involves an optimization problem: an appropriate function \(f(a,b)\) captures the quality of the fit for a line with slope \(a\) and intercept \(b,\) and one optimizes it to find the line of best fit. For linear regression this optimization problem can be solved by hand.

Artificial neural networks (ANN) - such as Large Language Models (LLM) - are more sophisticated machine learning algorithms, many of which are however essentially of the same type as linear regression. Their input and outputs can be images, text, sound, etc, and their output is produced from a sophisticated transformation of the input whose details are specified by parameters - rather than just the two parameters \(a,b\) of the linear regression above, these can number in the hundreds, thousands, millions or billions. The quality of the output produced on a given human prepared dataset is measured by a function \(f(x_{1},\ldots,x_{\#\text{param}}),\) and the ANN is “taught” by using a numerical optimization algorithm to optimize \(f.\)

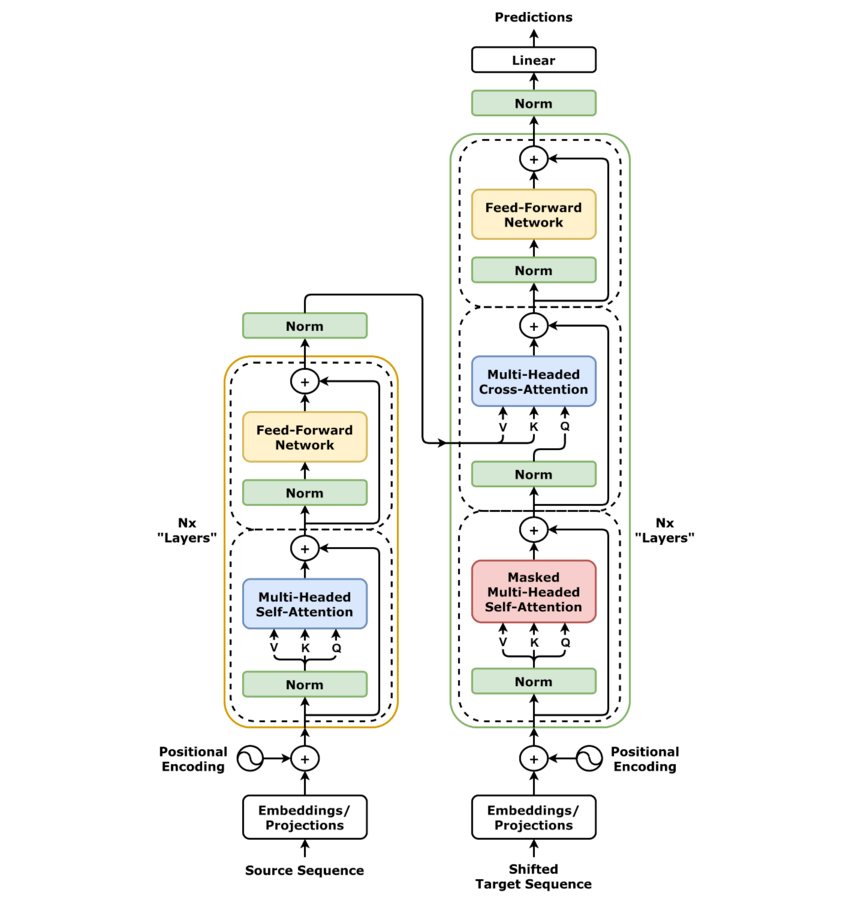

Architecture

Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Transformer,_full_architecture.png

\[\text{``Minimize }f(x_{1},\ldots,x_{\text{\#params}})\text{''}\]

“Learning” amounts to numerically optimizing a function \(f\) measuring the quality of the ANNs prediction on the dataset for given parameters \(x_{1},\ldots,x_{\text{\#params}}.\)

Optimization is an import aspect of machine learning, but ultimately it is only a means to the end of generalization. A machine learning algorithm generalizes if it produces “good” output for new inputs that are not in the dataset. Given how we expect rent to relate to floor area, the linear regression shown in Figure Figure 1.2 is likely to generalize well. But a machine learning algorithm based on polynomial interpolation applied to the same task dataset produces the prediction curve in the following figure.

This algorithm predicts wildly different rents for apartments of similar size, and even predicts negative rents for some sizes. For most apartment sizes not in the dataset the prediction is terrible, despite the prediction curve fitting the dataset perfectly. This is an example of poor generalization (the algorithm that produced the prediction in Figure Figure 1.4 doesn’t always generalize poorly, but in this situation it does). The goal of machine learning is to find an algorithm that generalizes well.

The first part of the course deals with optimization. Given a function \(f\) to optimize, the basic goal is to find the maximum or minimum of the function. You should already be familiar with the basic technique for solving such problems by hand: solving the critical point equation \(\nabla f=0.\) In the first chapter we will recall this technique, and several concepts from the courses Analysis I & II (formerly Calculus I & II) that are relevant to optimization (such as convexity).

In the second chapter we turn to constrained optimization, where one seeks to optimize the function \(f(x),\) but only among values of \(x\) that satisfy some set of constraints. After that we will study numerical optimization algorithms, which can be used for problems that are too large to solve by hand.

More precisely, this course is concerned with continuous optimization, that is the optimization of functions of continuous variables \(x\) (i.e. taking value in some interval of \(\mathbb{R}\)). By contrast, discrete optimization deals with the optimization of functions of variables that take a discrete set of values. The theory of discrete optimization is quite different from that of continuous optimization, and it is beyond the scope of this course.

2 Fundamentals

Although time-consuming, this is in fact the best way to study a mathematical text whether the proofs are new to you or not.

2.1 Global and local extrema of functions

First recall the concept of infimum and supremum of a subset of \(\mathbb{R}\): for instance \(\inf\:(-1,1)=\inf\:[-1,\infty)=-1,\) while \(\inf\:\mathbb{Z}=-\infty.\) In general the infimum of a set \(A\subset\mathbb{R}\) is the largest \(x\in\mathbb{R}\) s.t. \(a\ge x\) for all \(a\in A,\) or \(-\infty\) if no such \(x\) exists; the supremum is defined analogously. From this we get the concept of infimum and supremum of a function.

Let \(D\) be a set and \({f:D\to\mathbb{R}}\) a function with domain \(D\) and image \(f(D).\)

[Infimum]The infimum of \(f\) is \[\inf_{x\in D}f(x):=\inf f(D)\in\mathbb{R}\cup\{-\infty\}.\]

[Supremum]The supremum of \(f\) is \[\sup_{x\in D}f(x):=\sup f(D)\in\mathbb{R}\cup\{\infty\}.\]

Optimization problems are about finding the infimum or supremum of functions. Next recall the related concept of global minimum/maximum.

Let \(D\) be a set, \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) a function and \(x\in D\) a point.

[Glob. min.]The point \(x\) is a global minimizer or global minimum point if \[f(x)\le f(y)\quad\forall y\in D.\] We denote the set of all global minimizers by \(\mathrm{argmin}f\subset D.\) If a global minimizer \(x_{*}\in\mathrm{argmin}f\) exists we call \(f(x_{*})\) the global minimum value of the function and write \[\min_{y\in D}f(y):=f(x_{*}).\]

[Glob. max.]The point \(x\) is a global maximizer or global maximal point if \[f(x)\ge f(y)\quad\forall y\in D.\] We denote the set of all global maximizers by \(\mathrm{argmax}f\subset D.\) If a global maximizer \(x_{*}\in\mathrm{argmax}f\) exists we call \(f(x_{*})\) the global maximum value of the function and write \[\max_{y\in D}f(y):=f(x_{*}).\]

[Glob. extremum]If \(x\) is a global minimizer or global maximizer we call it a global extremum.

When it is clear from context what is meant, global minimum can refer to either the global minimum point or global minimum value, and similarly for global maximum.

A function always has an infimum and supremum (possibly \(\pm\infty\)), but not always a global maximum and minimum (point or value). If global minimizers resp. maximizers exist, then their value coincide with the infimum resp. supremum. That is, \(\inf_{x\in D}f(x)\) and \(\sup_{x\in D}f(x)\) are always defined, but \(\min_{x\in D}f(x)\) and \(\max_{x\in D}f(x)\) are not always defined - when \(\min_{x\in D}f(x)\) is defined then \(\inf_{x\in D}f=\min_{x\in D}f(x),\) and similarly for \(\max_{x\in D}f(x).\) The number \(|\mathrm{argmin}f|\) of global minimizers can be zero, one, \(\ge2\) or even infinite, as can the number \(|\mathrm{argmax}f|\) of global maximizers. See Figure 1.1 for some examples for functions with \(D\subset\mathbb{R}.\)

Next we recall the concept of local minimum/maximum.

Let \(D\) be a set and \(\rho\) a metric on \(D.\) Let \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) be a function and \(x\in D\) a point.

[Loc. min.]The point \(x\) is called a local minimum if there is a \(\delta>0\) s.t. \(f(x)\le f(y)\) for all \(y\in D\) with \(\rho(x,y)\le\delta.\) It is a strict local minimum if there is a \(\delta>0\) s.t. \(f(x)<f(y)\) for all \(y\in D\setminus\{x\}\) with \(\rho(x,y)\le\delta\) .

[Loc. max.]A point \(x\in D\) is called a local maximum if there is a \(\delta>0\) s.t. \(f(x)\ge f(y)\) for all \(y\in D\) s.t. \(\rho(x,y)\le\delta.\) It is a strict local maximum if there is a \(\delta>0\) s.t. \(f(x)>f(y)\) for all \(y\in D\backslash\{x\}\) s.t. \(\rho(x,y)\le\delta.\)

[Loc. extremum]If a point \(x\in D\) is a (strict) local minimum or maximum we call it a (strict) local extremum.

Though the definition is stated at the level of generality of metric spaces, the course will mainly (maybe only) deal with functions with domain \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1,\) which are metric spaces with the usual Euclidean distance \(\rho(x,y)=|x-y|.\) Then e.g. the condition for \(x\) to be a local minimizer is that there exists a \(\delta>0\) s.t. \(f(x)\le f(y)\) for all \(y\in D\) with \(|x-y|\le\delta.\)

Obviously, every global extremum is also a local extremum. The converse is not true. A function can have zero, one or several local minimizers/maximizers. See Figure 1.2 for some examples.

2.2 Critical points

Under appropriate conditions, a local or global extremum of a function \(f\) is a critical point of \(f.\) For instance, if \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) is differentiable, then any local extremum \(x\) is a critical point (i.e. \(f'(x)=0\)). Furthermore if \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) is twice differentiable and \(x\in\mathbb{R}\) is s.t. \(f'(x)=0\) and \(f''(x)>0,\) then \(x\) is a local minimizer. In this section we will recall these and related facts for functions \(f\) with domain \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1.\)

Recall that for \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1,\) and a differentiable function \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) the gradient \(\nabla f(x)\) at \(x\in D\) is the vector \[\nabla f(x)=(\partial_{1}f(x),\ldots,\partial_{d}f(x))\in\mathbb{R}^{d},\] consisting of the first order partial derivatives of \(f.\) If \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) is twice differentiable, the Hessian \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) at \(x\in D\) is the symmetric \(d\times d\) matrix \[\nabla^{2}f(x)=\left(\begin{matrix}\partial_{11}f(x) & \ldots & \partial_{1d}f(x)\\ \ldots & \ddots & \ldots\\ \partial_{d1}f(x) & \ldots & \partial_{dd}f(x) \end{matrix}\right)\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times d},\] consisting of all the second order mixed partial derivatives.

(Critical. point) Let \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1,\) and \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}.\) If \(x\in D\) and there is a open neighborhood \(U\) of \(x\) such that \(f|_{D\cap U}\) is differentiable, and \[\nabla f(x)=0\] then we call \(x\) a critical point of \(f.\)

(Saddle point)If \(x\in D\) is a critical point of \(f\) which is not a local extremum of \(f,\) we call \(x\) a saddle point.

Informally, Taylor expansion to second order for an \(f\) with domain \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d}\) \[f(y)=f(x)+(y-x)\cdot\nabla f(x)+(y-x)^{T}\frac{\nabla^{2}f(x)}{2}(y-x)+\ldots.\] Stated rigorously, Taylor’s theorem for a continuously differentiable function \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) on an open domain \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1\) says that \[\lim_{y\ne x,y\to x}\frac{|f(x)+(y-x)\cdot\nabla f(x)-f(y)|}{|y-x|}=0\quad\text{for any}\quad x\in D.\tag{2.4}\] If in addition \(f\) is twice continuously differentiable, then for any \(x\in D\) \[\lim_{y\ne x,y\to x}\frac{|f(x)+(y-x)\cdot\nabla f(x)+(y-x)^{T}\frac{\nabla^{2}f(x)}{2}(y-x)-f(y)|}{|y-x|^{2}}=0.\tag{2.5}\]

We now carefully state the conditions under which a local extremum is a critical point. For any set \(A\) in a topological space, let \(A^{\circ}\) denote its interior (so that e.g. the set \(A=[0,1)^{2}\) in the topology of \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) has interior \(A^{\circ}=(0,1)^{2}\)).

Lemma 2.6. Let \(d\ge1,\) \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d}\) and let \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) be a continuously differentiable function. If \(x\in D^{\circ}\) and \(x\) is a local extremum of \(f,\) then \(\nabla f(x)=0.\)

Proof. Let \(x\in D^{\circ}\) be a local extremum of \(f.\) Applying Taylor’s theorem ([eq:ch1_taylor_first_order]) to \(f\) restricted to \(D^{\circ},\) we obtain that \[f(x+\Delta)\le f(x)+\nabla f(x)\cdot\Delta+|\Delta|r(\Delta)\] for \(\Delta\in\mathbb{R}^{d}\) small enough so that \(x+\Delta\in D^{\circ},\) where \(r(\Delta)\) is a function s.t. \(\lim_{\Delta\to0}r(\Delta)\to0.\) If \(\nabla f(x)\ne0,\) then with \(v=-\frac{\nabla f(x)}{|\nabla f(x)|}\) and \(\Delta=\varepsilon v\) it follows that \[f(x+\varepsilon v)\le f(x)-\varepsilon|\nabla f(x)|+\varepsilon\overline{r}(\varepsilon)=f(x)-\varepsilon(|\nabla f(x)|-\overline{r}(\varepsilon)),\] where \(\overline{r}(\varepsilon)=r(\varepsilon\Delta)\to0\) as \(\varepsilon\downarrow0.\) There is a \(\delta>0\) s.t. \(\overline{r}(\varepsilon)<|\nabla f(x)|\) for \(\varepsilon\le\delta,\) which implies that the r.h.s. is strictly smaller than \(f(x).\) Thus \[f(x+\varepsilon v)<f(x)\quad\text{for all }\quad\varepsilon\in(0,\delta),\] proving that \(x\) is not a local minimizer. An analogous argument proves that \(x\) can not be a local maximizer. We have shown that if \(\nabla f(x)\ne0,\) then \(x\) is not a local extremum. This implies the claim of the lemma.

The converse is not true, since a point \(x\) s.t. \(\nabla f(x)=0\) may be a saddle point rather than a local extremum. Furthermore the condition that \(x\) lie in the interior of \(D\) is necessary, since if \(D\ne\mathbb{R}^{d},\) then there may exist local minima on the boundary \(\partial D\) that are not critical points, as in the last plot of Figure 1.2.

Next we consider the relationship between the second derivative(s) and properties of local extrema. We write \(A>B\) for \(d\times d\) matrices \(A,B\) if \(x^{T}(A-B)x>0\) for all \(x\in\mathbb{R}^{d}\setminus\{0\},\) and \(A\ge B\) if \(x^{T}(A-B)x\ge0\) for all \(x\in\mathbb{R}^{d}.\) In the expressions \(A>0\) and \(A\ge0\) the r.h.s.s. are interpreted as the matrix with all entries equal to zero.

Lemma 2.7. Let \(d\ge1,\) \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d}\) and let \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) be a twice continuously differentiable function. Assume \(x\in D^{\circ}\) and \(\nabla f(x)=0.\)

a) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) is positive definite (i.e \(\nabla^{2}f(x)>0\)), then \(x\) is a strict local minimum.

b) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) is negative definite (i.e \(\nabla^{2}f(x)<0\)), then \(x\) is a strict local maximum.

c) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) has a negative eigenvalue, then \(x\) is not a local minimum.

d) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) has a positive eigenvalue, then \(x\) is not a local maximum.

e) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) has both positive and negative eigenvalues, then \(x\) is a saddle point.

Proof. a) Assume that \(x\in D^{\circ},\nabla f(x)=0\) and \(\nabla^{2}f(x)>0.\) By Taylor’s theorem ([eq:ch1_taylor_second_order]) there is a function \(r(\Delta)\) s.t. \(\lim_{\Delta\to0}r(\Delta)=0\) and \[f(x+\Delta)=f(x)+\Delta^{T}\frac{\nabla^{2}f(x)}{2}\Delta+|\Delta|^{2}r(\Delta)\:\forall\Delta\in\mathbb{R}^{d}\text{ s.t. }x+\Delta\in D^{\circ}.\tag{2.6}\] Since \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) is positive definite, there is an \(a>0\) s.t. \[\Delta^{T}\nabla^{2}f(x)\Delta\ge a|\Delta|^{2}\quad\text{for all }\quad\Delta\in\mathbb{R}^{d}.\] Thus \[f(x+\Delta)\ge f(x)+\frac{a}{2}|\Delta|^{2}+|\Delta|^{2}r(\Delta)\ge f(x)+|\Delta|^{2}\left(\frac{a}{2}-|r(\Delta)|\right)\] for \(\Delta\) s.t. \(x+\Delta\in D^{\circ}.\) Since \(\lim_{\Delta\to0}r(\Delta)=0\) there a \(\delta>0\) s.t. \(|r(\Delta)|\le\frac{a}{4}\) whenever \(|\Delta|\le\delta.\) This implies that \[f(x+\Delta)\ge f(x)+|\Delta|^{2}\frac{a}{4}>f(x)\quad\text{for all }\quad\Delta\text{ s.t. }0<|\Delta|\le\delta.\] Thus we have proved that \(x\) is a strict local minimum. The proof of a) is complete.

The claim b) is proved analogously with reverse inequalities, or by applying a) to \(x\to-f(x).\)

c) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) has a negative eigenvalue, then let \(v\) be a corresponding unit eigenvector. Using ([eq:ch1_crit_point_sec_deriv_taylor_use]) for \(\Delta=\varepsilon v\) one can show that \(f(x+\varepsilon\Delta)<f(x)\) for all small enough \(\varepsilon>0,\) which means \(x\) can not be a local minimum.

d) This follows by applying the argument of c) with inequalities reversed, or applying c) to \(x\to-f(x).\)

e) This is a direct consequence of c,d).

If \(\nabla f(x)=0\) and \(\nabla^{2}f(x)=0\) then \(x\) can be a local minimum, a local maximum or neither, and these different possibilities can not be distinguished using only information about the first and second derivatives at \(x.\) Similarly, if \(\nabla f(x)=0\) and \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\ne0,\nabla^{2}f(x)\ge0\) (so that \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) has both zero and a positive number as eigenvalues), then we can neither rule out that \(x\) is a local minimum, nor confirm that it is such a local minimum - but we can rule out that it is a local maximum.

2.3 Convexity and concavity

Convexity (or concavity) is very useful when optimizing. For instance, as well recall below, for convex function all local minimizer are guaranteed to be global minimizers. First recall the concept of a convex set.

Let \(V\) be a vector space over \(\mathbb{R}\) or \(\mathbb{C}.\) A subset \(A\subset V\) is convex if the line segment between any two points \(x,y\) in \(A\) is contained in \(A,\) i.e. if \[\theta x+(1-\theta)y\in A\quad\text{for all }\quad x,y\in A,\theta\in[0,1].\]

We will mainly (maybe only) consider convex subsets of the vector spaces \(V=\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1.\)

Next we recall the concept of convexity and concavity of functions.

Let \(V\) be a vector space over \(\mathbb{R}\) or \(\mathbb{C},\) and let \(D\subset V\) be a convex set.

[Convex func.]A function \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) is convex if \[\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y)\le f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\:\ \text{for all}\:\ x,y\in D,\theta\in[0,1].\] The function is strictly convex if this inequality holds strictly for all \(x,y\in D,\theta\in(0,1).\)

[Concave func.]The function \(f\) is concave if \[\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y)\ge f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\:\ \text{for all}\:\ x,y\in D,\theta\in[0,1],\] (i.e. if \(-f\) is convex), and strictly concave if the inequality holds strictly for all \(x,y\in D,\theta\in(0,1)\) (i.e. if \(-f\) is strictly convex).

Again, we will mainly and maybe only consider convex/concave functions when \(D\subset V=\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1.\)

Now we turn to the aforementioned property of the extrema of convex resp. concave functions.

Lemma 2.12. Let \(d\ge1,\) let \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d}\) be a convex set and \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) a function. Let \(x\in D.\)

a) If \(f\) is convex, then \(x\) is local minimizer iff it is a global minimizer.

b) If \(f\) is strictly convex , then \(f\) has at most one local and global minimizer.

c) If \(f\) is concave, then \(x\) is local maximum iff it is a global maximizer.

d) If \(f\) is strictly concave, then \(f\) has at most one local and global maximizer.

Proof. a) Assume \(f\) is convex, and assume for contradiction that \(x\in D\) is a local minimizer which is not a global minimizer. Then there is a \(y\in D\) s.t. \(f(y)<f(x).\) By convexity \[f(\varepsilon x+(1-\varepsilon)y)\le\varepsilon f(x)+(1-\varepsilon)f(y)\quad\forall\varepsilon\in[0,1].\] Since \(f(y)<f(x)\) we have \[\varepsilon f(x)+(1-\varepsilon)f(y)<f(x)\quad\forall\varepsilon\in(0,1].\] Thus \[f(\varepsilon x+(1-\varepsilon)y)<f(x)\quad\forall\varepsilon\in(0,1],\] which contradicts \(x\) being a local minimizer.

b) Assume \(f\) is strictly convex, and assume for contradiction that \(x,y\in D\) are distinct global minimizers. Then \(\min_{z\in D}f(z)=f(x)=f(y).\) By strict convexity \[f(\varepsilon x+(1-\varepsilon)y)<\varepsilon f(x)+(1-\varepsilon)f(y)\forall\varepsilon\in(0,1).\] The r.h.s. is just \(\min_{z\in D}f(z),\) so for instance for setting \(\varepsilon=\frac{1}{2}\) we obtain that \[f\left(\frac{x+y}{2}\right)<\min_{z\in D}f(z),\] where \(\frac{x+y}{2}\in D.\) This contradicts the definition of global minimum value. Thus there are no distinct \(x,y\in D\) that are both global minimizers, so \(f\) has at most one global minimizer.

c,d) This follows by reversing the inequalities in the argument for a,b) above, or applying a,b) to \(x\to-f(x).\)

A strictly convex function can can have zero or one global minimizer, while a non-strictly convex function can have zero, one, several or infinitely many global minimizers. The set of global minimizers must be convex. It can not have any local minimizers that are not global minimizers. For concave functions the same applies to maximizers. The next figure shows some examples.

Next we recall that the sum and maximum of convex functions is again a convex function, and the sum and minimum of concave function is again a concave function.

Lemma 2.13. a) If \(f_{1},f_{2}\) are convex functions with the same domain then \(f_{1}+f_{2}\) and \(\max(f_{1},f_{2})\) are convex functions. More generally, for a set \(I\) of any cardinality (including uncountable) and a family \(f_{i},i\in I,\) of convex functions indexed by \(i\in I,\) all with the same domain \(D,\) the function \[x\to\sup_{i\in I}f_{i}(x)\] with domain \(D_{I}=\{x\in D:\sup_{i\in I}f_{i}(x)<\infty\}\) is a convex function.

b) If \(f_{1},f_{2}\) are concave functions with the same domain then \(f_{1}+f_{2}\) and \(\min(f_{1},f_{2})\) are concave functions. For a set \(I\) of any cardinality and a family \(f_{i},i\in I,\) of concave functions indexed by \(i\in I\) all with the same domain \(D,\) then the function \[x\to\inf_{i\in I}f_{i}(x)\] with domain \(D_{I}=\{x\in D:\inf_{i\in I}f_{i}(x)>-\infty\}\) is a concave function.

Proof. a) If \(f_{1},f_{2}:D\to\mathbb{R}\) are convex then \(g=f_{1}+f_{2}\) satisfies \[\begin{array}{ccl} g(\theta x+(1-\theta)y) & = & f_{1}(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)+f_{2}(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\\ & \le & \theta f_{1}(x)+(1-\theta)f_{2}(y)+\theta f_{2}(x)+(1-\theta)f_{2}(y)\\ & = & \theta g(x)+(1-\theta)g(y), \end{array}\] for any \(x,y\in D,\theta\in[0,1].\) Thus \(g\) is convex.

Define \(h:D_{I}\to\mathbb{R}\) by \[h(x)=\sup_{i\in I}f_{i}(x).\] It satisfies \[\begin{array}{ccl} h(\theta x+(1-\theta)y) & = & \sup_{i\in I}f_{i}(x\theta+(1-\theta)y)\\ & \le & \sup_{i\in I}(\theta f_{i}(x)+(1-\theta)f_{i}(y))\\ & \le & \theta\sup_{i\in I}f_{i}(x)+(1-\theta)\sup_{i\in I}f_{i}(y)\\ & = & \theta h(x)+(1-\theta)h(y), \end{array}\] for any \(x,y\in D,\theta\in[0,1].\) Thus \(h\) is convex.

The claim b) follows by changing the direction of the inequalities in the arguments above, or by applying \(a)\) to \(x\to-f_{i}(x).\)

Next we recall that for sufficiently differentiable functions, convexity is equivalent to having everywhere non-negative second derivative in the univariate case, and more generally everywhere positive semidefinite Hessian. Concavity is equivalent to non-positive second derivative or more generally to everywhere negative semi-definite Hessian.

Lemma 2.14. Let \(d\ge1\) and let \(D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d}\) be open and convex. Assume \(f:D\to\mathbb{R}\) is twice continuously differentiable.

a) The function \(f\) is convex iff \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\ge0\) for all \(x\in D.\)

b) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)>0\) for all \(x\in D,\) then \(f\) is strictly convex.

c) The function \(f\) is concave iff \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\le0\) for all \(x\in D.\)

d) If \(\nabla^{2}f(x)<0\) for all \(x\in D,\) then \(f\) is strictly concave.

Note that a,c) are “iffs”, but not b,d). Indeed for instance \(f(x)=x^{4}\) is strictly convex, but \(f''(0)=0,\) so the converse of b) (and d)) is not true. Optional exercise: prove that \(f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{R}\) is strictly convex iff \(f''(x)\ge0\) for all \(x\in\mathbb{R}\) and \(f''(x)=0\) for at most one \(x\in\mathbb{R}.\)

Proof. \(a)\implies\) Assume \(f\) is convex. For any \(x\in D,\) Taylor’s theorem ([eq:ch1_taylor_second_order]) states that \[f(x+\Delta)=f(x)+(\nabla f(x))\cdot\Delta+\frac{\Delta^{T}\nabla^{2}f(x)\Delta}{2}+|\Delta|^{2}r(\Delta)\tag{2.9}\] for all \(\Delta\) s.t. \(x+\Delta\in D,\) where \(r\) is a function such that \(\lim_{\Delta\to0}r(\Delta)=0.\) By the convexity of \(f\) \[\frac{f(x+\Delta)+f(x-\Delta)}{2}\ge f(x)\] for all \(\Delta.\) Combining with ([eq:ch1_convexity_sec_deriv_charac_use_of_taylor]) we get that \[f(x)+\Delta^{T}\frac{\nabla^{2}f(x)}{2}\Delta+|\Delta|^{2}\frac{r(\Delta)+r(-\Delta)}{2}\ge f(x)\] or equivalently \[\frac{\Delta^{T}\nabla^{2}f(x)\Delta}{|\Delta|^{2}}\ge-(r(\Delta)+r(-\Delta)).\] For any unit vector \(v\) we can set \(\Delta=\varepsilon v\) and take the limit \(\varepsilon\downarrow0\) to obtain \[v^{T}\nabla^{2}f(x)v\ge0.\] Since this holds for all unit vectors \(v,\) it follows that \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\ge0.\)

\(a)\impliedby\) Assume \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\) is everywhere positive semidefinite. Let \(x,y\in D\) and consider \[g(\theta)=f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)-(\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y)),\theta\in[0,1].\] Firstly \[g(0)=g(1)=0.\tag{2.10}\] Furthermore \[\begin{array}{ccl} \frac{d}{d\theta}f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y) & = & \sum_{i=1}^{d}\partial_{i}f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y))\cdot\frac{d}{d\theta}\left\{ \theta x_{i}+(1-\theta)y_{i}\right\} \\ & = & \sum_{i=1}^{d}\partial_{i}f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y))(x_{i}-y_{i})\\ & = & (\{\nabla f\}(\theta x+(1-\theta)y))\cdot(x-y). \end{array}\] Taking another derivative we obtain \[\begin{array}{ccl} \frac{d^{2}}{d\theta^{2}}f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y) & = & \frac{d}{d\theta}\sum_{i=1}^{d}\partial_{i}f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y))(x_{i}-y_{i})\\ & = & \sum_{j=1}^{d}\sum_{i=1}^{d}\partial_{ij}f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)(x_{i}-y_{i})\frac{d}{d\theta}(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\\ & = & \sum_{j=1}^{d}\sum_{i=1}^{d}\partial_{ij}f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)(x_{i}-y_{i})(x_{j}-y_{j})\\ & = & (x-y)^{T}\{\nabla^{2}f\}(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)(x-y). \end{array}\] Thus \[g''(\theta)=(x-y)^{T}(\{\nabla f\}(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)(x-y),\] so \(g''(\theta)\ge0\) for all \(\theta\in[0,1].\) Thus \(g'\) is non-decreasing. By the mean value theorem there is a \(\theta_{*}\in[0,1]\) such that \(g'(\theta_{*})=0.\) Since \(g'\) is non-decreasing this means that \(g'(\theta)\le0\) for \(\theta\in[0,\theta_{*}]\) and \(g'(\theta)\ge0\) for \(\theta\in[0,\theta_{*}].\) This and ([eq:ch1_convexity_sec_deriv_charac_g_at_endpoints]) implies that \(g(\theta)\ge0\) for all \(\theta\in[0,1],\) proving that \[f(\theta x+(1-\theta)y)\ge\theta f(x)+(1-\theta)f(y),\theta\in[0,1].\] Since this holds for any \(x,y\in D,\) the function \(f\) is convex.

b) follows by reversing the inequalities in the argument above, or applying a) to \(x\to-f(x).\)

2.4 Simple optimization problems

Let us consider the general class of optimization problems \[\text{minimize }f,\text{ where }f:D\to\mathbb{R},D\subset\mathbb{R}^{d},d\ge1.\] Since maximizing \(f(x)\) is the same as minimizing \(-f(x),\) this form covers both minimization and maximization. We call the \(f\) to be optimized the objective function.

Consider the optimization problem \[\text{minimize }\frac{x^{4}}{4}-\frac{x^{2}}{2}\text{\,for }x\in\mathbb{R}.\tag{2.11}\] The objective function \(f(x)=\frac{x^{4}}{4}-\frac{x^{2}}{2}\) is infinitely differentiable with derivative \(f'(x)=x^{3}-x,\) so the critical point equation is \[x^{3}-x=0\iff x(x^{2}-1)=0\iff x\in\{0,-1,1\}.\] Thus \(f\) has the three critical points \(x\in\{0,-1,1\},\) and any local or global minimizers must belong to this set. Since \(f''(x)=3x^{2}-1\) is positive for \(x=\pm1\) and negative for \(x=0,\) we conclude that \(x=\pm1\) are local minimizers while \(x=0\) is a local maximizer. By symmetry \(x=\pm1\) yield the same value of the objective function, so they are global minimizers as long as one can not achieve a lower value of \(f\) by taking \(x\to\infty\) or \(x\to-\infty.\) Since the term \(x^{4}\) dominates as \(x\to\pm\infty\) we in fact have \(\lim_{x\to\pm\infty}f(x)=\infty.\) Thus \(x=\pm1\) are indeed global minimizers and the global minimum value of ([eq:ch2_example_1_opt_prob]) is \[f(\pm1)=\frac{1}{4}-\frac{1}{2}=-\frac{1}{2}.\]

Alternatively, instead of computing the second derivative one can simply compute \(f(x)\) at all critical points and compare the values. For this problem one gets \(f(0)=0\) and \(f(\pm1)=-\frac{1}{2},\) which allows one to rule out \(x=0\) as a global minimizer.

Consider the optimization problem \[\text{maximize }e^{-\frac{x^{2}}{2}}\left(\frac{x}{4}-x^{2}-1\right)\text{ for }x\in\mathbb{R}.\tag{2.12}\] We note that the objective function \[f(x)=e^{-\frac{x^{2}}{2}}\left(\frac{x}{4}-x^{2}-1\right)\] is infinitely differentiable, so any local or global maximizer must be a critical point \(x\) with \(f''(x)\le0.\) We compute \[f'(x)=e^{-\frac{x^{2}}{2}}\left(\frac{1}{4}-2x-\frac{x^{2}}{4}+x^{3}+x\right)=e^{-\frac{x^{2}}{2}}\left(x^{3}-\frac{1}{4}x^{2}-x+\frac{1}{4}\right).\] Thus the critical point equation \(f'(x)=0\) is equivalent to \[x^{3}-\frac{1}{4}x^{2}-x+\frac{1}{4}=0.\] By inspection we notice that \(x=1\) is a root of this polynomial, which can then by factored as \[(x-1)\left(x^{2}+\frac{3}{4}x-\frac{1}{4}\right)=0\] The quadratic \(x^{2}+\frac{3}{4}x-\frac{1}{4}\) has solutions \(x=-1\) and \(x=\frac{1}{4}.\) Thus all critical points of \(f\) are \[x=-1,\quad x=\frac{1}{4},\quad x=1.\] Simply evaluating \(f\) at these points we get the objective function values \[f(-1)=-\frac{9}{4}e^{-\frac{1}{2}},\quad f\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)=-e^{-\frac{1}{32}},\quad f(1)=-\frac{7}{4}e^{-\frac{1}{2}}.\] Note that clearly \(f(1)>f(-1).\) Also \(-e^{-\frac{1}{32}}\approx-0.97\) and \(-\frac{7}{4}e^{-\frac{1}{2}}\approx-1.06,\) so \(f(\frac{1}{4})>f(1).\) Thus \(x=\frac{1}{4}\) is the critical point with the smallest value. But \(\lim_{x\to\pm}f(x)=0>f\left(\frac{1}{4}\right),\) so in fact the value of ([eq:ch2_example_2_opt_prob]) of \(f\) is \(0,\) and there is no global maximizer.

Consider the optimization problem \[\text{minimize }\frac{1}{4}x^{4}-\frac{1}{2}x^{2}+\frac{1}{4}y^{4}-y^{2}-\frac{x^{2}y^{2}}{8}\text{ for }x,y\in\mathbb{R}.\tag{2.13}\] The objective function \[f(x,y)=\frac{1}{4}x^{4}-\frac{1}{2}x^{2}+\frac{1}{4}y^{4}-y^{2}-\frac{x^{2}y^{2}}{8}\] is infinitely differentiable and has gradient \[\nabla f(x,y)=\left(\begin{matrix}x^{3}-x-\frac{xy^{2}}{4}\\ y^{3}-2y-\frac{x^{2}y}{4} \end{matrix}\right).\] The critical point equation is thus the system \[\begin{cases} x^{3}-x-\frac{xy^{2}}{4} & =0,\\ y^{3}-2y-\frac{x^{2}y}{4} & =0. \end{cases}\] Factoring out \(x\) and \(y\) these turn into \[\begin{cases} x(x^{2}-1-\frac{y^{2}}{4}) & =0,\\ y(y^{2}-2-\frac{x^{2}}{4}) & =0. \end{cases}\] Thus \(x=y=0\) is a solution. A solution with \(x\ne0\) and \(y=0\) must satisfy \(x^{2}-1=0,\) so \((x,y)=(\pm1,0)\) are solutions. Similarly a solution with \(x=0\) and \(y\ne0\) must satisfy \(y^{2}-2=0,\) so \((x,y)=(0,\pm\sqrt{2})\) are solutions. Lastly a solution with \(x\ne0,y\ne0\) must satisfy \[\begin{cases} x^{2}-1-\frac{y^{2}}{4} & =0,\\ y^{2}-2-\frac{x^{2}}{4} & =0. \end{cases}\] This is a linear system in \(x^{2},y^{2}\) with unique solution \[x^{2}=\frac{8}{5},\quad\quad y^{2}=\frac{12}{5}.\] Thus \(\left(\pm2\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}},\pm2\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}\right)\) are also solutions. We have found a total of \(1+2+2+4=9\) critical points. Taking into account symmetries of \(f\) this reduces to the four solutions \((0,0),(1,0),(0,\sqrt{2}),\left(2\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}},2\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}\right).\) We attempt to classify them as local minimizers, maximizers or saddle points by considering the Hessian \[\nabla^{2}f(x,y)=\left(\begin{matrix}3x^{2}-1-\frac{y^{2}}{4} & -\frac{xy}{2}\\ -\frac{xy}{4} & 3y^{2}-2-\frac{x^{2}}{4} \end{matrix}\right).\] At \((x,y)=(0,0)\) we obtain \[\nabla^{2}f(0,0)=\left(\begin{matrix}-1 & 0\\ 0 & -2 \end{matrix}\right)\] which is negative definite, so \((0,0)\) is a local maximum. At \((x,y)=(1,0)\) we obtain \[\nabla^{2}f(1,0)=\left(\begin{matrix}2 & 0\\ 0 & -2 \end{matrix}\right)\] with positive and negative eigenvalues, so \((1,0)\) is a saddle point. At \((x,y)=(0,\sqrt{2})\) we obtain the negative definite \[\nabla^{2}f(0,\sqrt{2})=\left(\begin{matrix}-\frac{3}{2} & 0\\ 0 & -\frac{1}{2} \end{matrix}\right),\] so \((0,\sqrt{2})\) is a local maximum. Lastly at \((x,y)=\left(2\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}},2\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}\right)\) we obtain \[\nabla^{2}f(x,y)=\frac{2}{15}\left(\begin{matrix}8 & -\sqrt{6}\\ -\sqrt{6} & 12 \end{matrix}\right).\tag{2.14}\] The sign of the eigenvalues of ([eq:ch2_example_3_non_diag_hess]) can either by obtained by explicitly computing them, or by computing \[{\rm Tr}\:\left(\begin{matrix}8 & -\sqrt{6}\\ -\sqrt{6} & 12 \end{matrix}\right)>0\quad\text{and}\quad\det\left(\begin{matrix}8 & -\sqrt{6}\\ -\sqrt{6} & 12 \end{matrix}\right)=8\times12-6>0,\] and noting that a \(2\times2\) matrix with positive trace and determinant has two positive eigenvalues. This shows that \((x,y)=\left(2\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}},2\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}\right)\) is a local minimum. Thus our candidate for the value of ([eq:ch2_example_3_opt_prob]) is \[f(x,y)=\left(2\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}},2\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}\right)=-\frac{8}{5}.\] Before we can conclude that this is the minimum value, we must verify that one cannot achieve a lower value as the limit of a sequence \((x_{n},y_{n})\) diverging to infinity. We can do so by noting that the quartic terms in \(f(x,y)\) dominate as \(x,y\to\infty,\) and they satisfy \[\frac{1}{4}x^{4}+\frac{1}{2}y^{4}-\frac{x^{2}y^{2}}{8}\ge\frac{1}{4}\max(|x|,|y||)^{4}-\frac{\max(|x|,|y|)^{4}}{8}=\frac{\max(|x|,|y|)^{4}}{8}.\] Thus \(f(x,y)\to\infty\) as \((x,y)\to\infty,\) so the local minimizer \(\left(2\sqrt{\frac{2}{5}},2\sqrt{\frac{3}{5}}\right)\) is indeed a global minimizer, ([eq:ch2_example_3_opt_prob]) is \(-\frac{8}{5}.\)

Consider the optimization problem \[\text{Minimize }x^{3}-x^{2}+x^{2}y^{2}\quad\text{for}\quad x,y\in[-3,3].\tag{2.15}\] We note that the objective function \[f(x,y)=x^{3}-x^{2}+x^{2}y^{2}\] has domain bounded \[D=[-3,3]^{2},\] and is infinitely differentiable, so any local or global minimizer in \((-3,3)^{2}\) (the interior of \(D\)) must be a critical point \(x\) with \(\nabla^{2}f(x)\ge0.\) We compute \[\nabla f(x,y)=\left(\begin{matrix}3x^{2}-2x+2xy^{2}\\ 2x^{2}y \end{matrix}\right).\] Thus the critical point equation \[\nabla f(x,y)=0\] is equivalent to the system \[\begin{cases} 3x^{2}-2x+2xy^{2} & =0,\\ 2x^{2}y & =0. \end{cases}\] It is easy to see that \((0,y)\) is a solution for any \(y,\) and any solution \((x,y)\) with \(x\ne0\) must satisfy \(y=0\) and \[3x-2=0\iff x=\frac{2}{3}.\] Evaluating \(f\) at the solutions we obtain \[f(0,y)=0\ \forall y\quad\text{and}\quad f\left(\frac{2}{3},0\right)=-\frac{4}{27}.\] Thus \((x,y)=\left(\frac{2}{3},0\right)\) is the critical point with the lowest objective function value. But before concluding that this is the solution of ([eq:ch2_example_5_opt_prob]), we must consider \(f\) on the boundaries of \(D,\) that is for \(x=\pm3,y\in[-3,3]\) and \(x=[-3,3],y=\pm3.\) Evaluating \(f\) on these sets we obtain \[\begin{array}{lcc} f(3,y)=18+9y^{2}\ge0, & & f(-3,y)=-36+9y^{2},\\ f(x,3)=f(x,-3)=8x^{2}+x^{3}. \end{array}\] We see that on the boundary with \(x=3\) no value is achieved which “beats” \(f\left(\frac{2}{3},0\right)=-\frac{4}{27},\) but on the boundary with \(x=-3\) the point \((x,y)=(-3,0)\) achieves the strictly lower value \(f(-3,0)=-36.\) Finally to find the lowest point on the boundaries \(y=\pm3\) we must solve the optimization problem \[\text{Minimize }8x^{2}+x^{3}\text{ for }x\in[-3,3].\tag{2.16}\] We solve this by noting that the critical point equation is \[16x+3x^{2}=0\] with solutions \[x_{1}=0,\quad x_{2}=-\frac{16}{3},\] corresponding to the objective function values \[x_{1}^{2}+x_{1}^{3}=0,\quad8x_{2}^{2}+3x_{2}^{3}=x_{2}^{2}(8+3x_{2})=x_{2}^{2}\frac{56}{9}\ge0.\] Thus these do not “beat” the point \(f(-3,0)=-36.\) Before we conclude that this is the solution, we must check the boundaries of the “subproblem” ([eq:ch2_example_5_opt_prob_boundary_sub_problem]), noting that for \(x_{\pm}=\pm3\) we have \[-9=x_{-}^{2}(8+3x_{-})=8x_{-}^{2}+x_{-}^{3}<8x_{+}^{2}+x_{+}^{3}.\] Thus these points do not “beat” the point \(f(-3,0)=-36.\) We can conclude that the solution to ([eq:ch2_example_5_opt_prob]) is \(-36,\) achieved uniquely at \((x,y)=(-3,0).\)

Consider the optimization problem \[\text{Minimize }\:\frac{1}{2}p\log p+\frac{1}{2}(1-p)\log(1-p)+p\text{\,for }p\in[0,1].\] The solution can be simplified by noting that the objective function \[f:[0,1]\to\mathbb{R},\quad\quad f(p)=\frac{1}{2}p\log p+\frac{1}{2}(1-p)\log(1-p)+p\] is convex. Indeed, it is infinitely differentiable on \((0,1)\) with derivative \[f'(p)=\frac{1}{2}\log p-\frac{1}{2}\log(1-p)+\frac{1}{2}-\frac{1}{2}+1\] and second derivative \[f''(p)=\frac{1}{2p}+\frac{1}{2(1-p)}>0\text{ for all }p\in(0,1).\] Thus actually \(f\) is even strictly convex on \([0,1].\) This means that if a critical point of \(f\) exists, it is the global minimizer - we do not have to worry about the boundaries of \([0,1].\) We thus proceed to solve the critical point equation \[f'(p)=0\iff\frac{1}{2}\log p-\frac{1}{2}\log(1-p)+1=0\iff\frac{p}{1-p}=e^{-2}\iff p=\frac{1}{1+e^{2}}.\] Since we have successfully found a critical point of this convex function, we can already conclude that this is the global minimizer, giving global minimum value \[\begin{array}{ccl} f\left(\frac{1}{1+e^{2}}\right) & = & -\frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{1+e^{2}}\log(1+e^{2})-\frac{1}{2}\frac{e^{2}}{1+e^{2}}\log\left(\frac{1+e^{2}}{e^{2}}\right)+\frac{1}{1+e^{2}}\\ & = & \frac{e^{2}}{1+e^{2}}+\frac{1}{1+e^{2}}-\frac{1}{2}\log(1+e^{2})\\ & = & 1-\frac{1}{2}\log(1+e^{2}). \end{array}\]

To summarize, the take home message about this basic kind of optimization problem is: \[\text{Solve the critical point equation!}\] All the while: \[\begin{array}{c} \text{Remember to check for things that don't}\\ \text{show up as solutions to the critical point equation!}\\ \implies\text{extrema at boundaries}\\ \implies\text{infima/suprema achieved only as limits, rather than by global extrema.} \end{array}\]